The Fall Feasts of Israel

Excerpt from Jewish Roots of Christianity by Larry Stamm

We all like vacation getaways. We’ve all prepared for trips to desired destinations. Some preparations are more complicated and involved than others, yet the goal is the same—to arrive at the locale we’ve fancied, then enjoy all the benefits that place affords.

It’s been said that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a step. As we travel down Redemption Road, we come to a culmination of sorts as we approach the fall feasts of Israel. They are in order of observance: Rosh Hashanah, also known as the Feasts of Trumpets; Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement; and Sukkot, also called the Feast of Tabernacles or Booths.

As part of that spiritual culmination on the Jewish religious calendar, there are powerful threads of redemption with which the Christian can identify. These concepts will help us not only grow in our understanding of the person and work of Messiah Jesus, but will help us better appreciate the salvation we have through faith in Christ, our Lord.

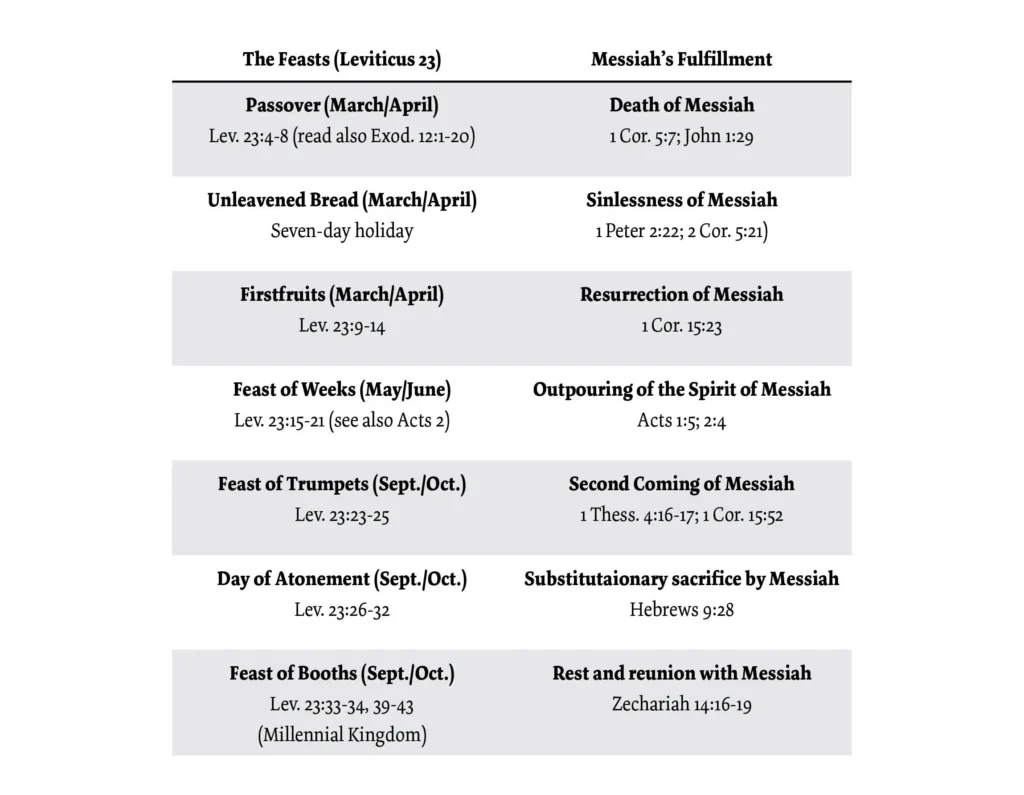

Before we dive into the fall feasts in particular, I want us to review this reality: each of the feasts of Israel find their ultimate fulfillment in the work of Messiah Jesus.

As we noted in Chapter 8, our study of the feasts of Israel began in Leviticus 23:1–2, “And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, ‘Speak to the children of Israel, and say to them: “The feasts of the Lord, which you shall proclaim to be holy convocations, these are My feasts.”’”

If you remember, the Hebrew word used here for “feasts” is the word moed which means “appointed time,” a time for people to stop everything and focus their attention on God, who He is and what He has done for them.

The chart below shows God’s institution of the feasts in Leviticus 23 along with corresponding New Testament passages highlighting their fulfillment in Messiah Jesus. A study of the material scriptures below will enhance understanding of the flow from Old Testament feast to New Testament fulfillment. Note the verses from Leviticus 23 are listed along with the general dates on our Gregorian (Christian or Western) calendar when the feasts occur.

Messiah Fulfills Israel’s Feasts

To review, remember also that the ancient Hebrews observed a twelve-month lunar calendar based on Psalm 104:19, where the scripture states, “He appointed the moon for seasons; The sun knows its going down.” They had elaborate protocol in place to precisely determine the new moon, so that the appointed times, or feasts, could be observed on the correct days.

The fall feasts of Israel occur in the seventh month on the Hebrew calendar, the sacred month of Tishri. The reason Tishri is called the “sacred month” is because it’s the seventh month on the Jewish calendar, and seven, as you may know, symbolizes divine perfection. It also contains the most holy days of any month on the Jewish calendar—hence the connection with culmination. Additionally, Tishri is the sabbatical month, and along with the seventh day of the week, was set apart as sacred.

The fall feasts are unique among God’s appointed times because they form a natural progression of thought. Mitch and Zhava Glaser note in their superb book, The Fall Feasts of Israel:

The Feast of Trumpets (Rosh Hashanah) teaches repentance; Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, redemption; and Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles or Booths, rejoicing. On the Feast of Trumpets, the sound of the ram’s horn calls upon each Jew to repent and confess his sins before his Maker. The Day of Atonement is that ominous day when peace is made with God. On the Feast of Tabernacles, Israel obeys God’s command to rejoice over the harvest and the goodness of God. It’s necessary to pass through repentance and redemption in order to experience His joy.” (The Fall Feasts of Israel by Mitch and Zhava Glaser; pg. 16; Copyright 1987; The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago; Moody Press-Publisher)

Now that we have our itinerary for this incredible stop on our journey down Redemption Road, let’s begin our excursion by delving into the Feast of Trumpets.

The Feast of Trumpets—Rosh Hashanah

God instituted this feast in Leviticus 23:23–25:

Then the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to the children of Israel, saying: ‘In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall have a sabbath-rest, a memorial of blowing of trumpets, a holy convocation. You shall do no customary work on it; and you shall offer an offering made by fire to the Lord.’”

The Feast of Trumpets, more commonly called Rosh Hashanah, marks the beginning of the civil year and is the Jewish New Year’s Day. This day begins what are known as the ten “days of awe,” a time when Jewish people examine their lives and repent of sins. When God gave the calendar of feasts to Israel, this feast wasn’t originally named. In Hebrew it was simply called Yom Truah, the day of blowing, the blowing of the trumpets. Why did the Lord institute this feast? He wanted to commemorate this sacred season with a trumpet blast to get the people’s attention!

Three things are traditionally observed on Rosh Hashanah. First, it’s a celebration of the New Year. You may wonder, “How can Rosh Hashanah be the New Year and occur in the seventh month?” That’s a good question. Rosh Hashanah literally means “head of the year” and marks the beginning of the civil year, not the biblical or religious year, which begins in the spring. A second prominent tradition on Rosh Hashanah is to remember Abraham’s binding of Isaac and God’s provision of the ram for sacrifice. A third tradition is the blowing of the shofar. The blowing of the shofar is a call to repentance, and it’s also a reminder of God’s covenant made with Israel at Mt. Sinai. The blowing of the shofar marks the beginning of the days of awe, a time of preparation of the heart for Yom Kippur.

The real theme of Rosh Hashanah is repentance. The Gemara, a collection of rabbinic thought on Judaism put together between the third and fifth centuries, states:

Three books are opened on Rosh Hashanah, one for the completely righteous, one for the completely wicked, and one for the average persons. The completely righteous are immediately inscribed in the book of life. The completely wicked are immediately inscribed in the book of death. The average persons are kept in suspension from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur. (Ibid, pg. 33.)

As you can imagine, most people fall into the “average” person category, not knowing exactly where they stand with God! During these ten days, traditional Jewish observers try to tip the scales in their favor so they can be inscribed in the book of life. Mitzvot, or good deeds, are done, like giving to the poor. Confessions are recited, and differences with others are resolved. The ceremony of Tashlich, the symbolic casting of sins into the water, follows afternoon services on Rosh Hashanah. A congregation will meet at a river or stream and empty their pockets, usually consisting of breadcrumbs, into the water. This a symbol of emptying themselves of sin. Tashlich is based on Micah 7:19, which says, “He will again have compassion on us, And will subdue our iniquities. You will cast all our sins Into the depths of the sea.”

Foods eaten on Rosh Hashanah are festive. Fruits and honeycakes are served. Apples and honey are also a traditional food enjoyed as a way of ushering in the New Year, a hopeful time where people desire the sweetness of life in the coming days. The most common greeting during the Jewish New Year season is, “L’shanah tovah tikatevu,” which means, “May your name be inscribed in the Book of Life.”

Growing up in St. Petersburg, Florida, I attended a Reform synagogue. Reform Judaism is a liberal branch of Judaism. As a youth I attended services on Rosh Hashanah with my family and chimed in greeting people with, “May your name be inscribed in the Book of Life,” while at the same time never pondering its significance. Why was that? In my Hebrew school studies as a youth, we didn’t speak much about the Book of Life. Reform and Conservative Judaism are modern expressions of Judaism and teach that the deceased continue to exist in the memories of the living. Only Orthodox Jews believe in a literal resurrection from the dead, and within the whole of Judaism, there is no uniform view of death and the afterlife. The sages speculate, but most Jewish people today are uncertain about life beyond the grave.

Where does the Book of Life come from? It’s referred to several places in the Hebrew scriptures, the Old Testament. Moses referred to the Book of Life in Exodus 32. Daniel 12 mentions it. David wrote in Psalm 69:28 about his enemies, “Let them be blotted out of the book of the living, And not be written with the righteous.” As believers in Jesus Christ, we understand that same Book of Life is where our names are inscribed. In Philippians 4:3, the Apostle Paul refers to the book, “And I urge you also, true companion, help these women who labored with me in the gospel, with Clement also, and the rest of my fellow workers, whose names are in the Book of Life.” Additionally, there are six verses in the book of Revelation that refer to the Book of Life. Specifically, in Revelation 3:5 Jesus promised that the names of all believers will not be erased from the Book of Life.

In Judaism, being in right relationship with God so that one can be inscribed in the Book of Life is certainly important from a biblical perspective, especially during the fall feast season. People want to be in right standing before God so they can be “happy” and “prosperous.” We who know Messiah Jesus know also that He is the giver of all good gifts, and the happiness and prosperity He provides transcend both circumstance and time!

Jesus came to bring abundant and eternal life! In John 11:25–26, He said, “… I am the resurrection and the life. He who believes in Me, though he may die, he shall live. And whoever lives and believes in Me shall never die. …” Since we who know the Lord are inscribed in the Book of Life, the Great Commission mandates us to go and tell others how they can have their names inscribed in the Book of Life. How? Not by righteous works we have done, but rather by trusting in Jesus and the righteous work on the cross he has accomplished for us! This is the basis of a right relationship with the Lord, and we know the beginning of that right relationship begins with repentance.

The Hebrew word Teshuvah, which can mean “to turn” or “to return,” conveys this idea of repentance. For the believer, this turning from our sinfulness and turning to the righteousness of God found in Jesus Christ through faith is the beginning of our walk with the Lord. For the Jewish community, this concept of repentance is central to the observance that begins at Rosh Hashanah and runs through the ten days of awe. So, Rosh Hashanah is all about repentance.

The Day of Atonement—Yom Kippur

After Rosh Hashanah, it’s with repentant hearts that Jewish people approach Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. This is the most awesome day, the tenth day of Tishri in the seventh month. The Lord instituted the Day of Atonement in Leviticus 23:26–32:

And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying: “Also the tenth day of this seventh month shall be the Day of Atonement. It shall be a holy convocation for you; you shall afflict your souls, and offer an offering made by fire to the Lord. And you shall do no work on that same day, for it is the Day of Atonement, to make atonement for you before the Lord your God. For any person who is not afflicted in soul on that same day shall be cut off from his people. And any person who does any work on that same day, that person I will destroy from among his people. You shall do no manner of work; it shall be a statute forever throughout your generations in all your dwellings. It shall be to you a sabbath of solemn rest, and you shall afflict your souls; on the ninth day of the month at evening, from evening to evening, you shall celebrate your sabbath.”

The Talmud, the Jewish oral law, simply refers to Yom Kippur as “The Day.” Jewish people fast all day and implore God for forgiveness. The Hebrew word yom means “day.” The Hebrew word kippur means “atonement,” which comes from the Hebrew word kapper, meaning “to cover.” As we’ve discussed, forgiveness of sins in the Old Testament was through the sacrificial system of atonement God gave Israel on the altar. The “life for life” principle is the foundation of the sacrificial system, specifically blood sacrifice.

Leviticus 17:11 states, “… I have given it to you upon the altar to make atonement for your souls; for it is the blood that makes atonement for the soul.” Blood is the symbol of life. The blood of bulls, lambs, and goats was to be sacrificed by the high priest. On Yom Kippur, special sacrifices were to be made by the high priest. In Leviticus 16, God describes how these sacrifices were to be offered. The high priest was to ceremonially cleanse himself, preparing to enter the Holy of Holies in the tabernacle. This was where the very presence of God dwelt. The high priest was to only enter the Holy of Holies one day a year, on Yom Kippur. First, he was to offer sacrifices on the alter and sprinkle blood on the mercy seat to atone for his sins. Then two male goats were to be chosen by lot. The priests were to slaughter one goat and sprinkle its blood on the mercy seat, trusting that God would accept the sacrifices as atonement for the people of Israel. The high point of the ritual was the ceremony involving the second goat, called the scapegoat, which is described in Leviticus 16:21–22, where the Lord said:

Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, confess over it all the iniquities of the children of Israel, and all their transgressions, concerning all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and shall send it away into the wilderness by the hand of a suitable man. The goat shall bear on itself all their iniquities to an uninhabited land; and he shall release the goat in the wilderness.

We noted that the central theme of Rosh Hashanah is repentance. The main theme of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is redemption. Redemption, meaning the price paid to purchase someone out of slavery, comes from the Hebrew word padah, which was accomplished through the sacrificial system God provided on the altar. The temple in Jerusalem was destroyed in a.d. 70, and in the years immediately following that event, the leaders of Judaism came up with a new way to obtain redemption, the forgiveness of sins, without the temple.

As noted, when we studied the gospel in the Old Testament, the solution—a magic formula for forgiveness which was developed by the rabbis, without the temple—is this: We are forgiven through prayer, repentance, and mitzvot, or good works—of which you’ll find many passages in the Old Testament. The underlying idea is that atonement and forgiveness depend on whether a man’s good deeds outweigh his bad deeds, but is that really the way to eternal redemption?

As a missionary to my Jewish people in New York City for six years (2003–2009), I often asked Jewish people how they are having their sins forgiven without a sacrifice. Some quoted the rabbis, but most simply didn’t have an answer. In fact, I’ve never had an unbelieving Jewish person tell me they walked out of the temple on Yom Kippur having assurance of forgiveness, nor has any sincere unbelieving Jewish person ever told me he has assurance his name is written in the Book of Life.

As believers in Messiah Jesus, we can have absolute assurance our sins are forgiven. Hallelujah! How does one find atonement without a temple? In Hebrews 9, the writer called Messiah Jesus our High Priest, and about His sacrificial death he wrote, “ Not with the blood of goats and calves, but with His own blood He entered the Most Holy Place once for all, having obtained eternal redemption” (v. 12). We don’t trust in our own good works, but rather in the finished work of Jesus Christ on the cross!

He offered Himself as our sacrifice for sin, and He conquered the power of both sin and death when He arose on the third day. And we affirm and echo the words of the Apostle Paul, who wrote in 1 Corinthians 15:55, “O Death, where is your sting? O Hades, where is your victory?” For those who believe in Jesus, forgiveness is found! On a deeper note, Old Testament sacrifice was good only for the covering of sins. The sacrifice of Jesus, our High Priest, cleanses us of all sin! Old Testament sacrifice was temporary. Each year, Yom Kippur was to be observed, but Jesus’ sacrifice was a one-time atonement. Jesus is my atonement today and every day; and in every way He has done it all for us! Now that’s something to rejoice about. And rejoicing is what the Feast of Tabernacles is all about!

The Feast of Tabernacles—Sukkot

We go back to Leviticus 23, where God instituted the last of the fall feasts, the Feast of Tabernacles:

Then the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to the children of Israel, saying: ‘The fifteenth day of this seventh month shall be the Feast of Tabernacles for seven days to the Lord. … Also on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, when you have gathered in the fruit of the land, you shall keep the feast of the Lord for seven days; on the first day there shall be a sabbath-rest, and on the eighth day a sabbath-rest. And you shall take for yourselves on the first day the fruit of beautiful trees, branches of palm trees, the boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God for seven days. You shall keep it as a feast to the Lord for seven days in the year. It shall be a statute forever in your generations. You shall celebrate it in the seventh month. You shall dwell in booths for seven days. All who are native Israelites shall dwell in booths, that your generations may know that I made the children of Israel dwell in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God.’” —Leviticus 23:33–34, 39–43

As the sun goes down marking the end of the Day of Atonement, Jewish people begin to build the Sukkah booth, preparing to celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles. In biblical times this was a joyful celebration of the final fall harvest, a time of ingathering at Jerusalem. It was the last of three feasts (along with Passover and Pentecost) when God commanded all males to come to Jerusalem. The Feast of Tabernacles or Sukkot (sukkot is a Hebrew word meaning “hut” or “booth”) also commemorates God’s deliverance of His people from Egypt and their forty years of wilderness wandering, when they lived in tents. God’s tabernacle was with them. Jewish observers remember and rejoice in God’s faithfulness and in His provision through the wilderness experience, so they build booths, or sukkahs and live in them for seven days. Even today, many Jewish people build open-roofed, three-sided huts for this festival. We decorate them with tree boughs and autumn fruits to remind us of the harvest.

One significant tradition that developed following God’s institution of Sukkot in Leviticus 23, which became very prominent in Jesus’ day, was called the “water pouring ceremony.” In it, the priests brought water from the pool of Siloam and poured it into the altar, praying for abundant rain that was needed for future harvests. Since Israel was an agrarian society at that time, rain was essential for survival, because if they didn’t get rains, they didn’t get harvests.

There was also a messianic significance to this ceremony, that looked toward the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Israel and the nations, too. The rain represented the Holy Spirit, and the water drawing pointed to that day when, according to the prophet Joel, God would rain His Spirit upon the Israelites. It’s no coincidence that as the Jewish people were thinking about God’s provision of rain for the harvest, and as they were celebrating and rejoicing in God’s presence in the symbol of water, Jesus chose this ceremony to stand up and speak these words in John 7:37–38, “… If anyone is thirsty, let him come to Me and drink. He who believes in Me, as the Scripture has said, out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.” We see Jesus using this symbol of water, something that Jewish people could see and understand, and applying it to His own life and ministry!

Sukkot, or the Feast of Tabernacles, also connects the dots between the temporal and eternal, as the Lord tabernacles with us through the person of the Holy Spirit. As we know, believers in Jesus are temples of the Holy Spirit, but the Bible also teaches us that sometime soon when the Lord returns, we as His church, the body of Messiah, will celebrate Sukkot for all eternity. As John wrote in Revelation 21:3–4:

And I heard a loud voice from heaven saying, “Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people. God Himself will be with them and be their God. And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain, for the former things have passed away.”

In that day, the whole world will become the Sukkah booth of God, and He will reign for all eternity. That will be a day of great rejoicing for all who know the love of Christ—both Jew and gentile alike! You and I, as believers in Jesus Christ, we also need to remember God’s faithfulness and provision and rejoice in His goodness to us. So, as believers in Jesus Christ, the progression of the fall feasts of Israel is also a picture of our faith journey—repentance from our sin, redemption found in Jesus, and rejoicing in our salvation.

So concludes our brief but beautiful tour through the feasts of Israel—all fulfilled in our Lord Jesus, our Great God! Hallelujah!

Larry Stamm is the founder and director of Larry Stamm Ministries, author of “Jewish Roots of Christianity” and a regular contributor to the Watchman on the Wall broadcast. He is a Jewish Christian in love with Jesus the Messiah and the Word of God. Larry Stamm Ministries exists to make the gospel of Jesus a confident topic of conversation for every Christian. www.larrystamm.org